Despite decades of CNC technology advancement, engine lathes remain the backbone of metalworking shops worldwide. From small hobby enthusiasts to Fortune 500 manufacturers, these precision machines continue to deliver unmatched versatility, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. An engine lathe is a powerhouse machine that rotates a workpiece while a cutting tool shapes it—the foundation of metal turning operations.

The reason is simple: engine lathes are irreplaceable for small-batch production, prototype development, tool repair, and precision work that demands operator skill and intuition. While CNC machines dominate high-volume manufacturing, manual engine lathes thrive where flexibility, lower capital investment, and adaptive problem-solving matter most.

Today’s engine lathe users span a broad spectrum: hobbyists building custom parts in home shops, tool room technicians fabricating specialized components, maintenance facilities repairing worn shafts and bushings, aerospace suppliers producing critical assemblies, and industrial plants maintaining production equipment. Whether you’re restoring antique machinery, manufacturing automotive components, or cutting custom threads, an engine lathe delivers precision and control that’s hard to beat.

This comprehensive guide explores everything you need to know about engine lathes—from fundamental specifications and operational uses to choosing the best model for your needs, maintaining long-term reliability, and finding exceptional deals on used machines.

What Is an Engine Lathe? (Beginner-Friendly + Expert Details)

Definition & Core Purpose

An engine lathe is a precision machine tool that removes metal through controlled rotation and cutting. The workpiece (typically a rod, shaft, or cylindrical part) is held securely in a rotating spindle, while a stationary cutting tool gradually shapes the material. The operator manually controls tool position, feed rate, and spindle speed—making engine lathes fundamentally different from automated CNC machines.

The term “engine lathe” historically refers to lathes powered by factory steam engines or electric motors (as opposed to foot-powered treadle lathes). Today, it simply means a manually operated metal lathe driven by an electric motor, capable of precision turning, threading, boring, and drilling operations.

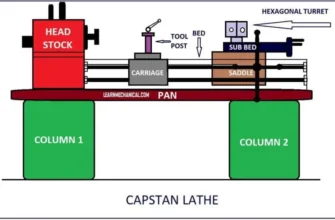

Key Components Every Operator Must Understand

Understanding engine lathe anatomy is critical for safe operation and informed purchasing decisions. Here are the essential parts:

Bed: The rigid, cast-iron foundation that supports all other components. The bed’s precision, hardness, and resistance to deflection directly determine machine accuracy and longevity. Hardened beds (often grind-finished) outlast softer castings and maintain tighter tolerances after years of production use.

Headstock: Houses the rotating spindle, bearings, and speed-change gearbox. The headstock’s spindle bore size (typically 1-1/2″ to 2″ diameter) determines the maximum drill size and collet compatibility. Quality headstocks feature precision ball bearings and robust spindle design to minimize runout.

Spindle: The rotating shaft that holds work-holding devices (chucks, collets, or face plates). Spindle speed ranges typically run from 40 RPM to 2000+ RPM, depending on machine class and gearbox design.

Carriage: Holds the cutting tool and moves along the bed under operator control. The carriage assembly includes the cross-slide (perpendicular movement), compound rest (angular adjustments), and toolpost (cutting tool mounting).

Tailstock: Provides support for long workpieces and can hold center drills, reamers, or taper attachments. The tailstock slides along the bed and locks in position to provide opposing support.

Leadscrew & Feed Rod: Drive automatic tool movement during threading and turning operations. The leadscrew (engaged through the carriage’s half-nuts) produces precisely coordinated thread pitches. The feed rod drives the carriage continuously during normal turning.

Ways: The precisely ground or finished bearing surfaces on the bed where the carriage and tailstock glide. Hardened ways resist wear and maintain accuracy; softer ways degrade faster under heavy production use.

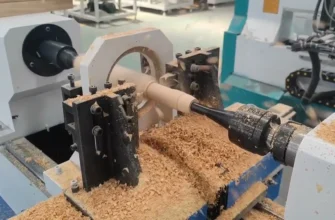

What Makes Engine Lathes Different from Bench, Turret & CNC Lathes

Bench Lathes are scaled-down models (typically 7″ to 10″ swing) designed for light hobby work, producing less than half the cutting power and workholding capacity of full-size industrial engine lathes. They’re suitable for small parts and educational settings but lack the rigidity for production work.

Turret Lathes (and automatic screw machines) feature preset tool positions and programmable operations, enabling rapid semi-automatic production of identical parts. However, they’re specialized for high-volume identical parts—not versatile like manual engine lathes.

CNC Lathes use computer control, sacrificing operator intuition and flexibility for speed and repeatability in high-volume runs. Setup costs are steep; best-case scenario is 500+ identical parts to justify programming time.

Manual Engine Lathes offer unmatched versatility: one machine handles turning, threading, drilling, boring, knurling, grooving, and complex one-off work. Setup is quick, tool changes are simple, and adaptive skill matters enormously.

Typical Workpieces Engine Lathes Handle

Engine lathes excel at producing:

- Shafts (automotive, industrial drive systems)

- Bushings, sleeves, and wear components

- Custom fasteners and studs

- Gun barrels and precision rifle components

- Pump impellers and compressor parts

- Tool steel dies and gauges

- Specialty threads (metric, pipe, acme)

- One-off prototype components requiring iteration

Engine Lathe Specs Explained: What Buyers Must Know

Selecting an engine lathe without understanding specifications is a recipe for disappointment. Here’s what separates adequate machines from precision powerhouses—and why each spec matters.

Swing Over Bed: The First Buying Decision

Swing over bed is the maximum workpiece diameter the lathe can rotate without hitting the bed. A 10″ lathe swings a 10″ diameter part; a 16″ lathe handles 16″ diameter work. Larger swing means heavier, more expensive machines but dramatically expands capability. For hobby work, 10″-12″ swing suffices; serious production shops typically choose 14″-20″ machines. European industrial standards often quote “swing over carriage” (slightly more, as the tool can extend above the carriage).

Distance Between Centers: Length Determines Part Capability

Distance between centers (DBC) specifies the maximum workpiece length that can be held between headstock and tailstock. Common sizes: 22″, 36″, 40″, or 60″ for full-size industrial lathes. Longer DBC means longer shafts and custom parts, but requires more floor space and typically higher cost.

Spindle Bore Size: Determines Drill & Collet Compatibility

The spindle bore (hole running through the spindle) determines maximum drill size and collet compatibility. Typical bore sizes: 1-1/4″ (small lathes), 1-1/2″, or 2″ (industrial). Larger bore = larger capacity but heavier spindle assembly.

Spindle Speeds & Gearbox Types: Performance Matters

Variable-speed electronic spindles (using VFD technology) offer infinitely adjustable RPM—ideal for optimizing feeds & speeds for different materials. Geared-head models use mechanical gearboxes with fixed speed ranges (typically 12-16 speeds), requiring manual engagement. Belt-driven lathes use pulley adjustments for quick speed changes but require motor shutdown to change belts.

Higher spindle speeds (1000+ RPM) suit smaller-diameter work and harder materials; lower speeds (100-500 RPM) provide more torque for heavy interrupted cuts on large-diameter steel.

Motor Power & Voltage: Don’t Underestimate This

A 2-3 HP motor suits hobby and small production shops. 5-7 HP handles serious industrial work with heavy cuts on steel. 10+ HP powers legacy heavy-duty industrial machines for continuous production. Single-phase 120V motors are rare (only tiny bench lathes); most machines run 240V single-phase (home/small shop) or 480V three-phase (industrial). Three-phase motors run cooler and more efficiently; single-phase requires larger capacitors.

Ways: Hardened vs. Non-Hardened Precision

Hardened ways (often Meehanite cast iron or proprietary hardened castings) resist wear and maintain tight tolerances after decades of production use. They’re standard on precision machines and command premium prices. Non-hardened ways degrade faster, losing accuracy as dirt and metal swarf embed in the softer surface. For heavily used production shops or long-term ownership, hardened ways justify the cost.

Threading Ranges & Feed Rates: Capability Checklist

Engine lathes typically cut threads from coarse (12 TPI) to extremely fine (100+ TPI). Check metric capability if you work internationally. Feed rates—how fast the carriage moves per spindle revolution—range from 0.003″ to 0.25″ per revolution on quality machines. Finer feeds provide better surface finish; coarser feeds remove material faster.

Weight & Build Quality: Why Heavier Is Usually Better

A well-designed 500-pound bench lathe outperforms a poorly-engineered 1200-pound machine—but generally, heavier industrial lathes indicate superior casting quality, more rigid bed construction, and better damping of vibration. The best engine lathes weigh 1000-4000+ pounds, absorbing vibration and maintaining tight tolerances under production stress.

Safety Features: Guards, E-Stop, and Certification

Modern engine lathes must feature chip guards, emergency stop buttons (E-stop), spindle brake, and rotating chuck guards. European CE-certified machines meet stricter safety standards than older American models. When buying used, verify guards are intact and functional—retrofitting proper guards is expensive and complex.

Uses of Engine Lathes: From Hobby Jobs to Heavy Industrial Work

Engine lathes accomplish far more than simple shaft turning. Here’s what they excel at:

Turning & Facing: The Core Operations

Turning reduces the outside diameter of a rotating workpiece by advancing a cutting tool perpendicular to rotation. Facing squares off the end of a part. Both operations are fundamental—you’ll perform them on virtually every job.

Thread Cutting: A Specialized Precision Skill

Engine lathes cut metric threads, unified threads, acme threads, tapered pipe threads, and specialty custom pitches. This capability—impossible on CNC without tremendous programming—gives engine lathes immense value for repair shops. Cutting a 1″-14 TPI thread on a damaged shaft that cost $2000 new? An engine lathe earns its space immediately.

Drilling, Boring, and Reaming: Expanding Capabilities

Hold a drill chuck in the tailstock, and your engine lathe becomes a precision drill press. Boring (enlarging existing holes to exact diameter and tolerances) is a core strength, especially for custom valve bodies, pump housings, or damaged bearing surfaces.

Knurling & Grooving: Adding Texture and Features

Knurling tools press a diamond pattern onto round stock for grip-friendly handles or mechanical locking surfaces. Grooving tools cut precise channels and shoulders—critical for O-ring grooves, snap-ring seats, or design features.

Production vs Precision Applications

Small job shops use engine lathes for low-volume precision work: aerospace brackets, custom automotive shafts, one-off prototypes. High-volume production (1000+ identical parts) demands dedicated turret lathes or CNC automation. Engine lathes shine in the sweet spot: 10-500 identical parts where setup simplicity and tool flexibility matter most.

Real-World Applications Prove Their Worth

Gun Barrels: Precision firearms manufacturers use heavy-duty engine lathes to bore and rifle custom barrels. The control and repeatability—combined with operator skill—produce match-grade accuracy.

Automotive Shafts: Custom driveshafts, transmission input shafts, and performance crankshafts often originate on engine lathes during prototyping or small-batch production.

Custom Bushings: Worn bearing surfaces on vintage machinery? An engine lathe fabricates replacement bushings in hours—often for under $200 in materials and labor.

Repair Shop Applications: A bent pump shaft, worn spindle, or damaged screw becomes a repair job (not replacement) thanks to engine lathe capability.

Types of Engine Lathes (Manual, Variable-Speed, Industrial Size, etc.)

Manual Engine Lathes: The Traditional Standard

Manual (geared-head) engine lathes use mechanical gearboxes with fixed speed ranges and require manual shift engagement. They’re rugged, simple to maintain, and excel in intermittent-duty environments. Examples: South Bend 9″, Logan 10×20, Clausing 5900 series. Cost: $500-$3,000 used; $2,000-$8,000 new.

Geared Head Lathes: Industrial Workhorse

Standard “geared head” lathes feature gear-driven main spindles with 12-18 discrete speed options. They’re the most common industrial engine lathe type—available in every size from 10″ to 20″+ swing. Durability is legendary; machines built in the 1950s-1980s still produce close tolerances.

Belt-Driven Lathes: Simplicity and Speed Flexibility

Older belt-driven models (common 1920s-1960s) use pulley systems for speed adjustment. They require motor shutdown to change belts—tedious but providing excellent speed range. Historical machines (South Bend, Logan, LeBlond) often use belt drive. Cost advantage: usually cheaper used; cost disadvantage: belt changes and less precise speed control.

Gap-Bed Engine Lathes: Large Workpiece Access

A removable section near the headstock allows short, large-diameter work to swing without hitting the bed. Gap-bed designs sacrifice some bed rigidity but enable facing large flanges or disk-shaped parts. Less common than standard beds due to slightly reduced accuracy potential.

Heavy-Duty Industrial Lathes: Production Monsters

Machines weighing 2000-6000+ pounds with 10-20 HP motors, massive cast beds, and hardened ways handle continuous production, heavy interrupted cuts, and harsh environments. Examples: Clausing Colchester, Poreba, Howa (Japanese). Cost: $5,000-$25,000 used; $15,000+ new.

Hobby & Bench Engine Lathes (10″, 12″, 13″)

Light-duty models (Grizzly G0602, Jet BDB-1340A, Precision Matthews PM-1030V) deliver surprising precision in compact packages. Ideal for home shops, tool & die work, and education. Cost: $800-$4,000 new.

Best Engine Lathe Machines: Top-Rated Models by Category

Best Manual Engine Lathes for Beginners & Small Shops

Grizzly G0602 (10×22): The hobby standard. 10″ swing, 22″ between centers, 1 HP, 2000 RPM top speed. Accuracy ±0.002″. Excellent for small parts, tool repair, and learning. Price: $900-$1,200. Limitation: modest power; not ideal for heavy steel cuts.

Jet BDB-1340A (13×40): A step up. 13″ swing, 40″ DBC, 2 HP, variable DC spindle (0-2000 RPM). Greater cutting capacity; better for serious hobby work. Price: $2,500-$3,500. Note: requires 240V single-phase.

Bolton Tools 12×36: Economical mid-range model. 12″ swing, 36″ DBC, 2 HP geared head, multiple speeds. Strong value for small shops starting out. Price: $1,800-$2,400 new. Limitation: basic accuracy; acceptable for production but not precision.

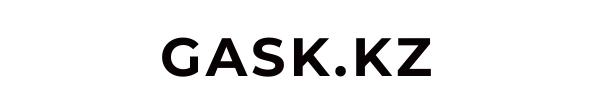

Best Industrial Engine Lathes for Professional Metalworking

Acer 1740G (17×40): Taiwanese precision lathe. 17″ swing, 40″ DBC, 3 HP geared head. Hardened ways, smooth feeds, proven accuracy. Price: $4,000-$6,000 used; $7,000+ new. Excellent reputation among tool & die shops and automotive suppliers.

Kingston HD Series (16″ or larger): British industrial heritage. Massive bed, hardened ways, exceptional rigidity. Larger machines weigh 2000+ pounds. Price: $6,000-$15,000 used (condition-dependent); rarely sold new. Outstanding for production shops.

LeBlond RKL Series (15×40 or larger): American classic. These mid-century workhorses remain popular because they’re so robust. 15″ swing, 40″ DBC, geared head, 2-3 HP. Price: $3,000-$7,000 used depending on condition. Excellent rebuild candidates.

Best Heavy-Duty Engine Lathes (Factory & Maintenance Shop Use)

Clausing 5900 Series: American production standard from 1970s-1990s. 16-20″ swing options, hardened ways, 5-7 HP, geared head. These machines handle serious steel cutting and run reliably for decades. Price: $5,000-$12,000 used. Investment value is strong—these machines hold utility and resale appeal.

Poreba Heavy Industrial (Polish manufacture): Enormous machines (20″+ swing, 80-120″ DBC) for large shaft work. Weighs 3000-5000 pounds. Price: $8,000-$20,000 used; challenging to transport. Best for shops committing to heavy fabrication.

Best Affordable & Budget-Friendly Engine Lathes

Precision Matthews PM-1030V: Modern Chinese import with excellent value. 10″ swing, 30″ DBC, variable-speed DC spindle (0-2000 RPM), 2 HP. Price: $1,500-$2,000 new. Strong among hobbyists; reasonable build quality.

Harbor Freight Central Machinery: Entry-level models under $1,000 new. Pros: Incredibly affordable; adequate for occasional hobby use. Cons: Loose tolerances (±0.01″ typical), basic accuracy, marginal build quality, limited spare parts availability. Only recommended for experimentation, not serious production.

Best Made-in-USA & Legacy Industrial Lathes

South Bend (various series): Indiana-built. 9″ to 16″ models from 1920s-1980s. Renowned for precision and durability. Used prices: $400-$3,000 depending on size and condition. Excellent for restoration projects and small shops.

Logan (American manufacture, various sizes): Similar era and reputation to South Bend. Often underpriced compared to equivalent South Bend machines. Used prices: $300-$2,000. Exceptional value for budget-conscious buyers.

Clausing Colchester (British heritage): Precision machines from 1950s-1970s. Known for tight tolerances and exceptional build quality. Used prices: $4,000-$10,000 depending on size. Still capable of production work requiring ±0.001″ tolerances.

Monarch (American heavy industrial): 16″ and larger machines, 1940s-1970s. Massive beds, extreme rigidity. Used prices: $6,000-$18,000. Best for shops committing to heavy production work.

Used Engine Lathes: How to Find Great Deals & Avoid Bad Machines

Advantages of Buying Used

Massive cost savings: A used Clausing 5900 ($6,000-$8,000) delivers nearly identical capability to a new Asian import ($12,000+). Historical quality: Machines built 1950-1980 were often engineered more robustly than modern budget models. Proven reliability: You can research user forums and read reviews from decades of operation. Lower depreciation: Industrial machines hold value; modest used machines often recover 60-80% of purchase price if you resell.

What to Inspect Before Buying

Threads & Gearbox Condition: Spin the lathe manually (motor off). Listen for grinding, scratching, or rough spots. Check spindle bearings for play (grab the spindle chuck and try rocking side-to-side; zero play is ideal). Run through all gear positions; each shift should be smooth and positive.

Wear on Ways: Use a straightedge along the bed length. Any visible gaps indicate worn ways (possible but not disqualifying if worn uniformly). Check for corrosion, pitting, or embedded metal swarf—these suggest poor maintenance history.

Backlash Levels: Reverse the carriage feed direction while watching the cutting tool. Any delay before motion reverses indicates gearbox or feed rod wear. Acceptable backlash: 0.003″ or less. Excessive backlash compromises accuracy; costly to repair.

Spindle Runout: Mount a dial indicator on the spindle nose. Rotate and measure runout (indicator deflection). Acceptable: under 0.002″ TIR (Total Indicated Runout). Worn bearings increase runout; replacement spindles or bearing sets typically cost $1,000+.

Electrical Condition: Test the motor (listen for humming, feel for vibration). Check wiring insulation (cracked insulation = safety hazard). Three-phase machines require VFD conversion for single-phase power ($1,500-$3,000). Verify voltage compatibility with your facility.

Price Ranges for Common Sizes (9″, 10″, 12″, 14″, 16″, 20″)

| Size | Condition | Expected Price Range |

|---|---|---|

| 9″ swing | Good condition | $300-$800 |

| 10″ swing | Good/excellent | $600-$1,500 |

| 12″ swing | Average/good | $1,000-$2,500 |

| 14″ swing | Good/excellent | $2,000-$5,000 |

| 16″ swing | Good/excellent | $3,000-$8,000 |

| 20″ swing | Industrial condition | $6,000-$15,000 |

Prices vary by brand (South Bend/Logan cheaper; Clausing/LeBlond higher), geographic location (urban areas command premiums), and specific condition.

Where to Buy Used Engine Lathes

SurplusRecord.com: Curated machinery listings from liquidations and shop closeouts. Extensive photos and specifications. No mediator; buyer and seller communicate directly. Highest prices but also highest quality average.

eBay Machinery Section: Massive inventory. Filter by location to minimize shipping. Verify seller feedback; request additional photos before bidding. Shipping negotiation critical (lathes are expensive to move).

Machinery Dealers (Wheeler Machinery, Revelation Machinery, Sterling Machinery): Professional buyers and rebuilders. Quality vetting and typically better documentation than private sellers. Higher prices but included transportation assistance.

Local Classifieds & Auctions: Craigslist, Facebook Marketplace, estate auctions. Lowest prices often here—but you’re responsible for inspection, negotiation, and transport. Time-intensive but rewarding for patient buyers.

Industrial Equipment Liquidators: Shop closures, bankruptcy auctions, and equipment downsizing. Call local liquidators and join their mailing lists. Auctions offer opportunities but require hands-on inspection pre-bidding.

How to Transport a Lathe Safely

Small lathes (10-12″ swing, under 800 lbs): Rent a box truck and pallet jack. Secure with tie-downs. $100-$300.

Mid-size lathes (14-16″ swing, 1000-2000 lbs): Professional machinery movers essential. Use a hydraulic forklift or boom truck. Cost: $500-$2,000 depending on distance.

Heavy industrial (20″+ swing): Specialized flatbed and rigging expertise required. Cost: $1,500-$5,000+. Obtain quotes from three machinery movers before committing.

Installation: Plan for solid concrete flooring and level mounting. Shims under feet are acceptable; bolting to floor is ideal for production use.

Engine Lathe Brands Compared (Modern & Legacy)

South Bend (American Heritage)

Era: 1920s-1980s primary production; some models still manufactured. Reputation: Legendary precision and durability. Models: 9″, 13″, 16″ swing versions. Typical Used Pricing: $400-$1,500. Why It Matters: Every machinist recognizes South Bend quality. Strong resale value; extensive online community support.

Logan (American Manufacture)

Era: 1910s-present (now acquired). Reputation: Comparable to South Bend; slightly less collectible, often cheaper. Models: 8″, 10″, 12″, 13″, 16″ varieties. Typical Pricing: $350-$1,200 used. Why It Matters: Excellent value; solid engineering; less “brand cache” than South Bend means lower prices for equivalent capability.

Mori Seiki (Japanese Precision)

Era: 1950s-present. Reputation: Modern precision; higher spindle speeds. Models: Various sizes, many with variable-speed spindles. Typical Pricing: $3,000-$8,000 used. Why It Matters: Smoother operation than vintage American machines; excellent for production.

LeBlond (American Industrial)

Era: 1920s-1970s primarily. Reputation: Heavy-duty construction; preferred by tool & die shops. Models: 13″, 15″, 16″, 20″ swing. Typical Pricing: $2,000-$6,000 used. Why It Matters: Exceptional rigidity; commands loyal following among experienced machinists.

Acer (Taiwanese Modern)

Era: 1980s-present. Reputation: Contemporary precision; good value. Models: 13″, 16″, 18″, 20″. Typical Pricing: $3,000-$8,000 used; $7,000-$15,000 new. Why It Matters: Reliable mid-range option; excellent for shops buying new.

Precision Matthews (Chinese Import, USA Support)

Era: 2000s-present. Reputation: Hobby-focused; excellent support for the price. Models: 10″, 12″, 13″, 16″. Typical Pricing: $1,500-$4,500 new. Why It Matters: Modern warranty, parts availability, and operator support make it popular among hobbyists and small shops.

Clausing (American & European)

Era: Various eras depending on model. Reputation: Exceptional build quality; industrial standard. Models: Clausing-made (USA) and Clausing Colchester (UK-made). Typical Pricing: $4,000-$12,000 used. Why It Matters: Among the finest machines ever built; commanding prices reflect legendary reputation.

European Industrial Brands (Tarnow, Poreba, Howa)

Tarnow (Polish): Mid-20th century, industrial-grade. Heavy and durable. Poreba (Polish): Large industrial machines; exceptional for heavy work. Howa (Japanese): Precision engineering; popular in European shops. Typical Pricing: $5,000-$20,000 used depending on size. Why It Matters: Less common in North America but respected by experienced machinists for rugged capability.

Engine Lathe Accessories & Tooling You Should Own

Chucks: The Critical Workholding Decision

3-Jaw Self-Centering Chuck: Holds round stock concentrically; fastest for repeated work. Available in Bison, Rohm, or generic brands. Cost: $100-$400 depending on quality.

4-Jaw Independent Chuck: Allows eccentric holding and precision setup of irregular parts. Essential for tool & die work. Cost: $150-$500.

Collet Chuck: Precise gripping of small-diameter work (3/8″ to 1″ typical). Requires matching collets. Cost: $200-$600 for chuck; $10-$25 per collet.

Recommendation: Start with a quality 3-jaw chuck; add a 4-jaw and collet chuck as your work demands them.

Toolposts (AXA, BXA, Wedge-Type QCTP)

AXA (smaller lathes) and BXA (larger lathes) are standardized quick-change toolpost sizes. Wedge-type toolposts are older but still excellent. QCTP systems ($200-$400) enable rapid tool changes without re-setup; far superior to traditional bolt-down toolposts ($20-$50).

Steady Rest & Follower Rest

Steady rest supports long, slender work in the middle to prevent deflection during turning. Follower rest supports work just behind the cutting tool. Cost: $150-$400 each. Essential for quality precision on long shafts.

Taper Attachment

Enables precise angled cuts and tapered workpieces. Cost: $300-$800 new; $100-$400 used. Highly specialized; not needed for basic turning.

Centers, Dogs, Drill Chucks

Live centers and dead centers ($20-$50 each) support workpieces between spindle and tailstock. Dogs ($10-$30 each) lock work to the spindle for rigid turning. Drill chucks ($30-$150) hold twist drills and reamers. These basics are essential.

Best Starter Tooling Kits + What Not to Cheap Out On

Purchase a quality QCTP system immediately—cheap toolposts create runout and frustration. Invest in decent cutting tools (carbide inserts, $5-$15 each) over cheap high-speed steel. A precision center drill set ($30-$80) is non-negotiable. Don’t skimp on chuck key quality—a broken key damages expensive chucks. Budget $500-$1,000 for initial tooling; you’ll add specialized tools as work demands them.

Engine Lathe Maintenance & Longevity Guide

Lubrication: The Foundation of Reliability

Engine lathe longevity depends entirely on consistent lubrication. Spindle bearings, gearbox, ways, and lead screw each require appropriate lubricants. Use spindle oil (light machine oil) for bearings, hydraulic fluid for power feeds, and way oil (heavy viscosity) for bed ways. Neglect = premature wear, lost accuracy, and expensive rebuilds. Establish a lubrication schedule—every 20-40 operating hours for light hobby use; daily for production shops.

Cleaning Routines: Prevent Accuracy Loss

Remove metal swarf and chips daily. Accumulation embeds in way surfaces, accelerating wear and increasing backlash. Use a chip brush and compressed air—never run bare hands near rotating spindles. Wipe ways with a clean rag weekly.

Checking Gearbox Oil

Most geared-head lathes use internal gearbox lubrication. Check oil level monthly; smell for burnt odor (indicates overheating or gear stress). Change oil annually (or per manufacturer spec). Cost: $20-$50 per oil change. Essential preventive maintenance.

Adjusting Gibs

Gibs are adjustable wear strips in the carriage-to-bed interface. Over time, wear creates play and lost accuracy. Tighten gibscrews gradually (1/4 turn at a time) until backlash disappears but carriage moves freely. Over-tightening damages ways. Requires patience and feel—ask experienced machinists for guidance on your specific machine.

Preventing Rust & Alignment Issues

Cover the lathe with a canvas or plastic sheet in humid environments. Apply light coat of way oil on bare steel during storage. Check alignment annually (especially after transport); bed twist causes tolerance creep. Use a precision level across the bed in multiple directions.

When to Regrind Ways

Professional way grinding ($3,000-$8,000) restores accuracy to worn machines. Only justified if you need sub-0.001″ tolerances and have high production volume. Most hobbyists and small shops work with existing wear.

How to Choose the Best Engine Lathe: A Buyer’s Decision Framework

For Hobbyists

Start with 10-12″ swing (Grizzly G0602, Jet BDB-1340A, or quality used South Bend). You’ll complete 95% of hobby projects. 22-30″ between-centers length handles most shafts. Budget $1,000-$3,000. Verify 240V single-phase availability at your shop. Prioritize variable-speed models (easier speed changes) and quality spindle bearings (indicator of overall build).

For Repair Shops

Buy 12-14″ industrial models with proven reliability (Clausing 5900, LeBlond RKL, Acer). You need durability, not maximum production capacity. Geared-head is acceptable (speed changes are infrequent). Prioritize machine condition; a well-maintained used machine outperforms a new budget model. Budget $3,000-$8,000 used.

For Industrial Production

Invest in 16-20″ heavy-duty machines (Clausing Colchester, Poreba, Monarch, or comparable). Maximum cutting power, hardened ways, and 10+ years of economical high-volume operation justify premium pricing. 40-60″ between-centers enables complex assemblies. Budget $8,000-$25,000+ for quality equipment.

Checklist: What to Buy, What to Avoid

Buy: Machines with documented maintenance history, hardened ways (for production), variable-speed spindles (if new), proven brands with community support, comprehensive tooling packages, recent electrical certification.

Avoid: Machines requiring complete restoration, seized spindles, severely corroded ways, missing E-stop or safety guards, machines requiring 480V three-phase (unless you have three-phase power), heavily used machines without detailed wear assessment.

Frequently Asked Questions (SEO-Optimized FAQ Section)

Where can I find a used metal lathe for a good price?

SurplusRecord.com, eBay machinery auctions, and local machinery dealers offer excellent inventory. Auctions and estate sales often yield best prices but require inspection before bidding. Building relationships with local equipment liquidators and joining their mailing lists ensures early access to deals. Patience and geographic flexibility expand your options significantly.

Is it better to buy a new metal lathe or an old one?

New machines offer warranty, modern spindle speeds, and consistent quality but cost significantly more (often 40-60% premium). Used industrial machines (1950-1980s) typically exhibit superior engineering and build quality compared to budget new imports. For precision work, a well-maintained vintage machine often outperforms new budget models. Hobbyists and shops on tight budgets benefit from quality used equipment; high-volume production shops justify new machines for warranty and parts support.

What are the best engine lathe brands?

Heritage American brands (South Bend, Logan, Clausing, LeBlond) remain highly regarded and hold resale value. Modern precision options include Acer, Mori Seiki, and Howa. Budget-conscious buyers appreciate Precision Matthews (excellent support) or Harbor Freight (accept limitations). Heavy industrial shops prefer Clausing Colchester, Poreba, or Monarch. Choose based on your application, budget, and availability in your region.

What size of lathe do I need?

Hobbyists: 10-12″ swing suffices for 95% of projects. Small shops: 12-14″ offers versatility without excessive cost or space. Production shops: 16-20″ with 40+ inch DBC handles complex assemblies and heavy cuts. Rule of thumb: Choose the largest machine your space and budget allow; capability grows into available machine size.

How do I get a used lathe home?

Small machines (under 800 lbs): Rent a box truck and use a pallet jack. Mid-size machines (1000-2000 lbs): Professional movers with hydraulic equipment ($500-$1,500). Large industrial machines: Specialized flatbed and rigging ($1,500-$5,000+). Plan transportation costs into your purchase budget; moving expenses rival machine cost for heavy equipment.

How to make money with an old metal lathe?

Repair services (custom shafts, bushings, threading) command $40-$150 per hour labor. Custom fabrication of specialized parts yields premium pricing. Gunsmithing services for barrel work and precision components. Freelance machine shop work through local connections or online platforms. Establish reputation through exceptional precision and reliability; word-of-mouth referrals from other professionals attract consistent work.

Conclusion

Engine lathes remain irreplaceable tools in modern metalworking despite decades of CNC advancement. Their versatility, lower initial cost, and operator control make them ideal for hobbyists, tool rooms, repair shops, and production facilities worldwide.

For hobbyists, a 10-12″ manual lathe like the Grizzly G0602 or quality vintage South Bend delivers decades of precision work and learning opportunity. For repair shops, industrial models (Clausing, LeBlond, Acer 1740G) provide robust capability for custom fabrication and emergency repairs. For production facilities, heavy-duty machines (Clausing Colchester, Poreba, Monarch) justify premium investment through reliable high-volume output.

Used markets offer exceptional value—machines built 1950-1980 with superior engineering often cost half of modern budget imports. Thorough inspection of spindle runout, way wear, and gearbox condition separates great deals from money-wasting mistakes. Patience and geographic flexibility unlock opportunities to acquire exceptional machines at reasonable prices.

Prioritize machine condition over brand prestige when buying used. Establish rigorous maintenance routines (lubrication, cleaning, gib adjustment) to preserve accuracy and extend equipment life. Invest appropriately in tooling—a quality QCTP system, cutting tools, and work-holding equipment make the difference between frustrating imprecision and professional-grade results.

Whether you’re cutting custom threads for restoration work, producing aerospace components, or building precision parts in your home shop, the right engine lathe becomes an irreplaceable partner in your metalworking journey. Choose thoughtfully, maintain diligently, and enjoy decades of reliable service.