A Modern Approach to CNC Milling

In the world of precision manufacturing, the ability to transform a solid block of material into a complex, three-dimensional component is a cornerstone of modern engineering. While traditional CNC machining excels at creating parts with flat surfaces and simple curves, the demand for intricate, contoured geometries has pushed the boundaries of what’s possible. This is where a specialized, advanced form of milling comes into play – a process known as Kellering. It represents the evolution from basic material removal to the artful sculpting of complex surfaces, enabling innovations from high-performance engine components to sophisticated aerospace parts. Kellering is derived from the legacy of Keller machines, pioneering systems that revolutionized three-dimensional milling and established the foundation for modern CAD/CAM-driven CNC technology.

The Evolving Landscape of CNC Machining

The CNC machining industry is a dynamic and expanding field with unprecedented growth. The global market for CNC milling machines is projected to reach USD 116.88 billion by 2034, growing from an estimated USD 84.86 billion in 2025, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.62%. This substantial expansion underscores the relentless demand for more precise and efficient manufacturing processes across industries. This growth is driven by the need to produce parts with increasingly complex designs, tighter tolerances, and superior surface finishes, pushing manufacturers beyond the limits of conventional 2.5-axis milling. The automotive sector alone utilizes over 130,000 CNC milling machines globally, highlighting the critical role of advanced machining technology in modern industrial production.

More significantly, five-axis CNC machining centers are experiencing rapid expansion, with projections indicating a 10.70% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) through 2030. This acceleration reflects the industry’s shift toward manufacturing increasingly complex components that require simultaneous multi-axis control – a capability that is central to the principles of Kellering and advanced contoured surface machining.

What is Kellering? A Concise Definition

At its core, Kellering is synonymous with 3D contoured surface milling – a sophisticated CNC machining process that focuses on creating complex, non-prismatic shapes by guiding a cutting tool along a multi-axis toolpath across a workpiece. Unlike standard milling operations that primarily work on X, Y, and Z planes with sequential passes, Kellering involves continuous, simultaneous movement in three or more axes to sculpt smooth, flowing surfaces; intricate cavities; and complex organic shapes. The term itself honors the pioneering Keller machines that first demonstrated this capability in the early 20th century, though modern implementations leverage advanced CAD/CAM software and CNC controls that far exceed the capabilities of mechanical tracer systems of the past.

Historical Context: The Keller Legacy

The origins of Kellering technology trace back to 1896, when Sidney and Joseph Keller established the Keller Mechanical Engineering Corp. in New York City. Initially designing and manufacturing precision silverware dies – a task that demanded extraordinary accuracy unavailable from American-made machines at that time – Joseph Keller, a skilled mechanical engineer, eventually constructed sophisticated machines for the company’s use.

The most significant innovation was the Keller duplicating machine, a tracer-controlled horizontal milling machine that could accurately replicate the contours of a template or master pattern. The machine featured an electric tracer (also called a tracing stylus or follower) that detected the physical shape of a template and translated this information into precise movements guiding the cutting tool. This innovation allowed for unprecedented accuracy in die and mold manufacturing. In 1930, Keller Mechanical Engineering Corp. merged with Pratt & Whitney, a partnership that proved essential to the aerospace and automotive industries during their formative years. The design principles of Keller’s machines formed the foundation for modern CAD/CAM and CNC systems.

Fast forward to the modern era: Roswitha and Siegfried Keller founded R. & S. KELLER GmbH in 1989 in Wuppertal, Germany, creating a leading provider of CNC simulation software, training programs, and CAD/CAM systems. Today, their company, now operating as CNC KELLER GmbH, serves over 7,000 customers across more than 70 countries, maintaining the Keller tradition of advancing CNC technology and education.

Why Kellering Matters in Today’s Manufacturing World

Kellering is not just another machining technique; it is an enabling technology that directly addresses contemporary manufacturing challenges. It allows designers and engineers to break free from the constraints of traditional manufacturing, creating parts that are lighter, stronger, and more efficient. For a manufacturer, mastering Kellering means being able to produce high-value components that were previously impossible or prohibitively expensive to make. It directly addresses the need for parts with optimized aerodynamics, fluid dynamics, or ergonomic profiles, making it indispensable in high-stakes industries where performance and precision are non-negotiable.

What You’ll Learn in This Guide

This guide will demystify Kellering, providing a comprehensive overview of its principles, mechanics, and real-world applications. We will explore how it differs from standard milling, detail the advantages it offers – from superior surface finish to extended tool life – and examine its crucial role in sectors like aerospace, automotive, and die manufacturing. By the end, you will understand what Kellering is, how it works, and why it has become a critical capability in modern CNC milling.

Demystifying Kellering: Core Concepts and Principles

To truly grasp the significance of Kellering, it’s essential to understand how it fundamentally differs from conventional approaches and the core principles that guide its execution. It represents a paradigm shift from simple material removal to intelligent surface sculpting.

The Essence of Kellering: Beyond Conventional Milling

The essence of Kellering lies in its ability to treat a workpiece not as a series of 2D profiles stacked together, but as a single, continuous 3D surface. Where conventional milling might create a pocket with a flat bottom and straight walls, Kellering can create a pocket with a smoothly curved floor that blends seamlessly into tapered walls. This process is less about cutting lines and more about “massaging” the material into its final, intricate form, creating features that are both functional and aesthetically refined.

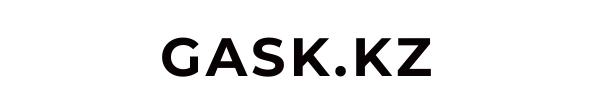

How Kellering Differs from Standard Milling Practices

Standard milling often involves 2.5-axis operations, where the cutting tool moves in X and Y simultaneously, then repositions along the Z-axis to cut at a new depth. Kellering, in contrast, typically requires 3-axis, 4-axis, or full 5-axis simultaneous machining. The key distinctions include:

Toolpath Complexity: Kellering toolpaths are far more complex, often consisting of thousands of small, coordinated movements that follow the precise topography of a digital model.

Axis Movement: It relies on simultaneous multi-axis movement, allowing the tool to remain normal (perpendicular) or at a specific angle to the contoured surface, which is crucial for finish quality and tool engagement.

Focus: Standard milling focuses on creating discrete features like holes, slots, and flat faces. Kellering focuses on generating holistic, complex surfaces.

Surface Integration: Rather than creating separate features that are then assembled, Kellering often produces integrated surfaces where multiple features flow seamlessly into one another.

Fundamental Principles Guiding Kellering Toolpaths

The creation of a Kellering toolpath is guided by several key principles designed to optimize the machining process. These principles are programmed into advanced CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing) software:

Constant Tool Engagement: The software aims to maintain a consistent amount of tool engagement with the material, which prevents shock loading, reduces tool wear, and helps maintain a uniform surface finish. This is particularly critical when machining difficult-to-cut materials like titanium or nickel-based superalloys.

Smooth, Flowing Paths: Toolpaths avoid sharp turns and sudden changes in direction. Instead, they use smooth arcs and splines to guide the tool, reducing machine stress and improving surface quality. This reduces chatter and vibration, which are primary causes of poor surface finish and premature tool wear.

Stock-Aware Machining: The CAM system is aware of the remaining material (stock) at all times, ensuring that each pass removes material efficiently without “cutting air” or overloading the tool. This optimization is essential for maximizing productivity while maintaining tool life.

Adaptive Depth of Cut: Advanced CAM systems dynamically adjust the depth of cut based on real-time feedback, preventing tool breakage and ensuring consistent material removal rates throughout the operation.

The Mechanics of Kellering: How it Works

The successful execution of Kellering operations depends on a tightly integrated system of advanced software, powerful CNC machines, and precise parameter control. This synergy transforms a digital design into a physically realized, complex component with exceptional accuracy and surface quality.

Advanced Toolpath Generation for Optimal Performance

Kellering begins with a 3D CAD model of the final part. This model is imported into CAM software, where a programmer defines the machining strategy. The software then generates the sophisticated toolpaths required for 3D contouring. Strategies like “scallop,” “spiral,” or “flowline” machining dictate how the tool moves across the workpiece surface:

- Scallop Milling: The tool moves in a pattern that creates small, uniform ridges (scallops) between passes. This strategy is ideal for finishing operations where surface finish is paramount.

- Spiral Machining: The tool follows a spiral or helical path, gradually stepping down as it moves across the surface. This creates a smooth, continuous cutting motion.

- Flowline Machining: The tool follows the natural contours of the surface geometry, much like water flowing around an obstacle. This strategy is particularly effective for organic or sculptural shapes.

The software calculates thousands of discrete points and vectors to create a continuous cutting motion that precisely matches the digital model’s topology. This dense coordinate information is then converted into G-code – the machine-readable language that directs the CNC controller.

Integration with CAM Software and CNC Controls

The CAM software is the brain behind the operation, translating the machining strategy into G-code – the language that CNC machines understand. Modern CAM packages like SYMplus™ (developed by CNC KELLER), Mastercam, Fusion 360, and others offer sophisticated algorithms for optimizing toolpaths specifically for 3D contoured surface machining. The G-code is then fed to the CNC controller, which directs the precise, synchronized movements of the machine’s axes, spindle, and other components. The seamless integration between the CAM system and the machine’s controller is critical for executing the complex and rapid actions required for Kellering without error.

Modern controllers with advanced look-ahead capabilities can process this dense code smoothly, preventing jerky movements and ensuring a high-quality finish. Controllers from manufacturers like Siemens (SINUMERIK), Fanuc, and Heidenhain offer specialized functions for managing the continuous, simultaneous multi-axis movements inherent in Kellering operations.

Key Parameters: Spindle Speeds, Feed Rates, and Tooling Selection

Achieving optimal results in Kellering requires careful selection and control of key machining parameters. These parameters must be balanced to prevent tool breakage, excessive heat generation, and poor surface finish while maximizing material removal rates and tool life.

Spindle Speed (RPM): The rotational speed of the cutting tool. Kellering typically employs high spindle speeds, often ranging from 3,000 to 15,000+ RPM, depending on the tool diameter and workpiece material. Smaller tools generally require higher speeds to achieve efficient cutting, while larger tools may operate at lower speeds to maintain proper surface speed. For finishing operations on difficult materials like Inconel, speeds are typically lower to reduce heat generation.

Feed Rate (IPM or mm/min): The speed at which the tool moves across the workpiece. This must be carefully balanced with spindle speed and depth of cut to avoid tool breakage and achieve the desired material removal rate. Modern Kellering typically employs high feed rates, sometimes exceeding 1,000 mm/min in roughing operations, but more conservative rates (100–300 mm/min) during finishing.

Depth of Cut (DOC): The amount of material removed in each pass. In Kellering, depths of cut are typically smaller than in conventional milling – often 0.5–2.0 mm – to maintain consistent tool engagement and prevent chatter.

Radial Depth of Cut (RDOC): In trochoidal and other advanced strategies, the radial engagement is specifically controlled to maintain a low, predictable tool load. This is often set to a fraction of the tool’s diameter to optimize both speed and tool life.

The Role of High-Speed Machining (HSM) and Trochoidal Milling

High-Speed Machining (HSM) is a technique often employed in Kellering. It uses high spindle speeds (often exceeding 10,000 RPM) paired with a lower radial depth of cut but a much higher feed rate. This approach reduces cutting forces, minimizes heat transfer into the workpiece, and allows for extremely fast material removal. For materials like aluminum and composites, HSM can achieve removal rates two to three times higher than conventional machining while producing superior surface finishes.

Trochoidal milling is a specific HSM toolpath strategy where the tool moves in a circular or “looping” pattern as it progresses along the surface. This ensures a consistent, low radial tool engagement, making it ideal for cutting deep pockets or slots in tough materials like titanium and nickel alloys without overloading the tooling. The benefits of trochoidal milling include:

- Consistent tool load: Prevents sudden spikes in cutting forces

- Reduced heat generation: Lower radial engagement means less friction

- Extended tool life: Predictable wear patterns allow for optimized tool selection

- Higher speeds and feeds: The controlled cutting conditions permit more aggressive parameters

Understanding the Underlying G-Code for Kellering Operations

While the CAM software automates G-code creation, understanding its structure reveals the complexity of Kellering. Instead of simple G01 (linear move) commands on two axes, a Kellering program is filled with thousands of tiny, simultaneous G01 moves across X, Y, and Z (and potentially A and B axes for 5-axis machines). This stream of continuous coordinate commands directs the machine to follow the contoured path, creating a smooth surface rather than a faceted one.

A typical Kellering operation might generate 5,000 to 50,000+ lines of G-code, each specifying precise XYZ coordinates (and possibly rotational axes) for each infinitesimal movement of the tool. This high density of coordinate data, combined with optimized feed rates, allows the machine to replicate the 3D surface topology with exceptional fidelity.

Advantages of Implementing Kellering in Production

Adopting Kellering as part of a company’s manufacturing processes provides a distinct competitive edge. The benefits extend beyond simply making complex parts; they impact efficiency, quality, and overall productivity in measurable ways.

Achieving Superior Surface Finish and Surface Roughness

Because Kellering toolpaths are designed for smooth, continuous engagement, they can produce an exceptional surface finish directly off the machine. The ability to use ball-end mills and maintain a constant step-over distance results in a surface with minimal cusp height – the ridges left between passes. In conventional milling with a ball-end mill and a 1 mm step-over, cusp height might be 0.008 mm. Through optimized Kellering strategies, this can be reduced to 0.001 mm or less, dramatically reducing or eliminating the need for secondary finishing operations like grinding or hand-polishing, lowering the overall cost and lead time for a finished part. Surface roughness (Ra) values of 0.4 µm or better are routinely achievable, comparable to ground or polished surfaces.

Enhancing Precision and Machining Tolerances

The controlled, continuous nature of Kellering allows for incredibly high precision. By minimizing tool deflection and maintaining consistent cutting forces, the process can achieve very tight tolerances on complex, free-form surfaces. Tolerances of ±0.02 mm on complex curved surfaces are standard in production settings, with specialized applications achieving ±0.005 mm or tighter. This level of accuracy is essential for components where fit and function are critically linked to surface geometry, such as in molds, turbine blades, and medical implants. The repeatability of Kellering also ensures that every part produced meets specifications, reducing scrap rates and rework.

Maximizing Metal Removal Rate and Overall Efficiency

Through the application of HSM and optimized toolpaths, Kellering can achieve very high Metal Removal Rates (MRR) – the volume of material removed per unit time. Strategies like trochoidal milling allow a machine to cut deeply and quickly without exceeding the tool’s limits. For aluminum, MRR values of 50+ mm³/min per millimeter of tool diameter are achievable, compared to 10–20 mm³/min in conventional milling. This efficiency means that the bulk of material from the initial block can be removed in significantly less time, freeing up valuable machine capacity for additional production runs and reducing overall manufacturing cost per part.

Extending Tool Life Through Optimized Engagement

One of the most significant long-term benefits of Kellering is improved tool life. Standard milling often subjects tooling to inconsistent loads, with the tool entering a corner and suddenly engaging 180 degrees of material. Kellering toolpaths are designed to maintain a constant, programmed radial engagement. This predictable load prevents chipping, reduces wear, and dissipates heat more effectively, allowing a single cutting tool to last significantly longer and perform more reliably. In some applications, tool life can be extended by 50–100% compared to conventional milling, substantially reducing tool costs over time.

Reducing Cycle Times for Increased Productivity

By combining high MRR in roughing operations, eliminating secondary finishing operations, and extending tool life (reducing downtime for tool changes), Kellering directly contributes to shorter overall cycle times. For complex aerospace components, Kellering can reduce cycle times by 30–50% compared to traditional multi-setup machining. For a manufacturer, this means higher throughput, increased productivity, and the ability to take on more jobs with the same equipment.

Capability for Machining Large, Complex Shapes

Historically, creating large dies or molds was a painstaking process requiring multiple setups and specialized machines. The principles of Kellering, once associated with specialized tracer machines, are now applied on large-scale CNC gantry mills with working areas exceeding 6 meters × 3 meters. This allows for the efficient machining of massive, complex components, such as automotive stamping dies, large-scale aerospace molds, and injection mold cavities, from a single block of material in a single setup. This capability reduces lead times, improves accuracy, and lowers overall manufacturing cost for large, intricate parts.

Practical Applications of Kellering in Various Industries

The ability to create complex, precise, and highly finished surfaces makes Kellering a vital process across numerous high-tech industries.

Aerospace Components: Precision and Material Challenges

In the aerospace sector, performance is paramount. Kellering is used to machine critical components including:

Impellers and Compressor Blades: Kellering creates the complex, aerodynamically optimized blade geometries in jet engine compressors. The precise surface finish reduces turbulence and improves engine efficiency.

Blisks (Bladed Disks): A blisk is a single component integrating both the rotor disk and blades as one part, rather than as a disk with removable blades. Blisks are lighter, more efficient, and more reliable than traditional assembled rotors. Blisk technology was first introduced in 1985 for the T700 helicopter engine compressor by Sermatech-Lehr (now GKN Aerospace). Since then, use has expanded to engines like the GE F110 turbofan, the Eurofighter EJ200, and the Pratt & Whitney Geared Turbofan (GTF). Machining blisks from solid titanium or nickel alloys requires sophisticated 5-axis CNC capability and precise control – exactly what Kellering provides. Modern blisk manufacturing also employs precision electrochemical machining (PECM), where material is dissolved using an electric current and chemical electrolyte, allowing for extremely precise shaping of difficult-to-machine superalloys.

Complex Structural Airframe Parts: Wing ribs, fuselage components, and other structural elements often feature complex curvatures optimized for aerodynamic efficiency or internal fluid routing. Kellering enables these shapes to be produced with exceptional precision and surface finish.

Kellering is used to machine components from high-strength alloys like titanium and Inconel, materials that are challenging to machine but essential for aerospace applications due to their strength-to-weight ratios and high-temperature performance.

Automotive Industries: Efficiency and Complex Geometries

The automotive industry relies heavily on CNC machining, with over 130,000 CNC milling machines used globally in the sector. Kellering plays a key role, particularly in high-performance applications:

Piston Domes and Combustion Chambers: Kellering is used to machine complex piston domes to precisely match combustion chamber shapes, maximizing volume and optimizing compression ratios for greater engine power and efficiency. The smooth, contoured surfaces reduce turbulence and improve combustion efficiency.

Underhead Milling (UHM): This is a specialized Kellering application where material is removed from the inside (underside) of a piston to optimize its thickness and weight distribution. By removing unnecessary material from areas that don’t experience high stress, manufacturers can reduce piston weight by 5–15 grams per piston without compromising strength. This weight reduction has cascading benefits – reduced inertia improves acceleration, and reduced reciprocating mass stress on connecting rods and crankshafts extends engine life. This technique is particularly popular in high-performance racing engines.

Complex Cooling Passages: Modern engines feature intricate internal cooling channels that can only be efficiently machined through 5-axis Kellering. These channels reduce combustion chamber temperatures and improve efficiency.

Electric Vehicle Components: As the automotive industry transitions to electric vehicles, Kellering is used to machine complex motor housings with integrated thermal management channels and precision mounting surfaces.

Die Shops: Crafting Intricate Molds and Specialty Dies

Kellering is the backbone of modern tool and die manufacturing:

Injection Molds: Complex cavities with fine details, undercuts, and detailed surface textures require Kellering’s precision. The high-quality surface finish means the mold surface often requires minimal or no secondary polishing, saving significant time and labor.

Stamping Dies: Large automotive stamping dies feature complex geometry to shape sheet metal into hoods, fenders, and other body panels. Kellering enables these dies to be produced with exceptional dimensional accuracy and surface finish.

Silverware and Specialty Dies: The precision die-making tradition pioneered by the Keller family in the 1890s continues today. Intricate patterns on dies used to stamp decorative silverware, jewelry, and specialty components require the exquisite precision and surface quality that Kellering provides.

Manufacturing Precision CNC Machined Parts Across Sectors

Beyond these specific examples, Kellering is applied wherever complex shapes are needed:

- Medical Industry: Custom implants, orthopedic components, and surgical instruments with complex anatomical shapes

- Energy Sector: Turbine components, compressor blades, and specialized fluid-handling components

- Consumer Electronics: Ergonomic aluminum housings, heat sinks, and precision mechanical components

- Optics and Precision Instruments: Lens mounts, precision mechanical assemblies, and specialized housings

Specific Features Best Suited for Kellering

Kellering excels at creating features that are difficult or impossible with standard methods:

Deep Pockets with Tapered Walls: Machining deep cavities, especially with complex floor geometry and sloped or curved sidewalls.

Blended Surfaces: Creating smooth, seamless transitions (fillets and radii) between different surfaces, eliminating sharp edges that could concentrate stress or cause tool breakage during assembly.

Free-Form Contours: Sculpting organic, non-geometric shapes for ergonomic or aerodynamic purposes – like the curved surfaces of a turbine blade or the contoured interior of an aerospace component.

“Massaging” Sharp Edges: Replacing sharp intersections with smooth, blended radii, which improves part strength, provides a finished component right out of the machine, and reduces assembly-related damage.

Complex Undercuts and Overhangs: Creating features that extend beneath or over other surfaces, which would be impossible or extremely difficult to machine with standard methods.

Role in 3D Milling Applications

Ultimately, Kellering is the practical application of 3D milling. It is the set of techniques and strategies that enables CNC machines to move beyond simple 2D shapes and truly sculpt in three dimensions. As the demand for more complex parts grows, and as multi-axis machines become more accessible – with 5-axis and above machines projected to grow at a 10.70% CAGR through 2030 – the role and importance of Kellering will only continue to increase.

Conclusion

Kellering, or 3D contoured surface milling, represents a critical evolution in CNC machining. It honors the pioneering work of the Keller family – from Joseph Keller’s early tracer-controlled machines of the 1900s to Roswitha and Siegfried Keller’s modern CNC training and CAM software – while representing the cutting edge of modern manufacturing technology. It bridges the gap between digital design and physical reality for the most complex components, moving beyond simple material removal to become a process of precision sculpting.

By leveraging advanced CAM software, sophisticated toolpaths, and multi-axis CNC machines, Kellering delivers unparalleled benefits in surface finish, precision, and efficiency. Modern implementations incorporate High-Speed Machining (HSM), trochoidal milling strategies, adaptive toolpath generation, and real-time monitoring systems that would have seemed like science fiction just decades ago.

For manufacturers, adopting Kellering is not just an upgrade in capability but a strategic necessity to compete in demanding sectors like aerospace, automotive, and high-performance engineering. It enables the creation of lighter, stronger, and more efficient parts, reduces cycle times, and extends tool life, directly impacting the bottom line. For designers and engineers, it removes traditional manufacturing constraints, unlocking new possibilities for innovation. For production facilities, investment in Kellering-capable equipment positions them to capture high-value manufacturing work in an increasingly sophisticated global marketplace.

As manufacturing processes continue to advance and automation becomes increasingly integrated with artificial intelligence and Industry 4.0 principles, the fundamental principles of Kellering – intelligent, multi-axis material removal optimized for precision and efficiency – will remain fundamental to creating the high-performance, intricately shaped components that define modern technology. Whether in jet engines, automotive powerplants, precision medical devices, or specialized industrial equipment, Kellering represents the marriage of engineering sophistication with manufacturing precision.

References and Data Sources

CP-Carrillo: Piston Manufacturing and Underhead Milling (UHM) Technology

Coherent Market Intelligence: CNC Milling Machines Market

Precedence Research: CNC Milling Machines Market (2025-2034)

Straits Research: CNC Milling Machines Market (2024-2032)

Mordor Intelligence: CNC Machines Market and 5-Axis Machining Growth

Metal Forming Magazine: The History of 3D Milling in the Die Shop (Poly Archives, NYU Libraries)

MTU Aero Engines: Blisk Development and Manufacturing Technologies

CNC KELLER GmbH: Company History and Software Development Timeline

Aerospace Manufacturing & Design: Blisk Milling and Jet Engine Blade Production